Globalization is still flat - and that's not necessarily bad

Martin Sandbu is optimistic about the outlook for globalization in 2017. While his colleague at the Financial Times Shawn Donnan recently wrote about globalization in countries' policies (on which I commented yesterday), Mr. Sandbu looks at globalization in outcomes, in the sense of growing economic integration between countries.

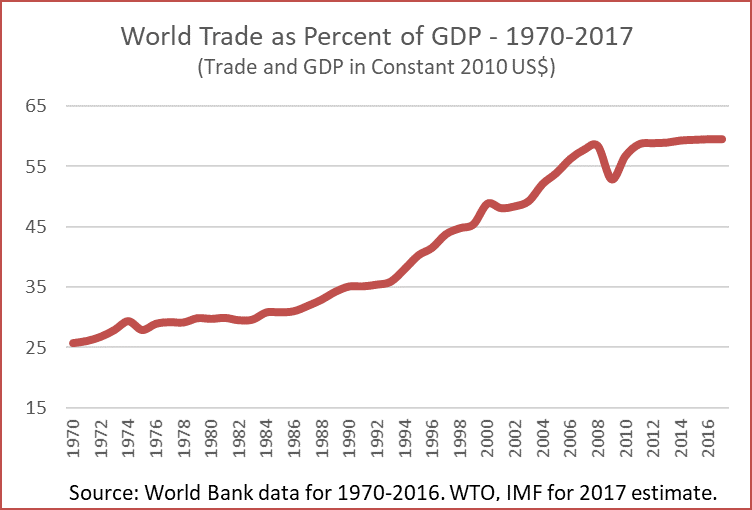

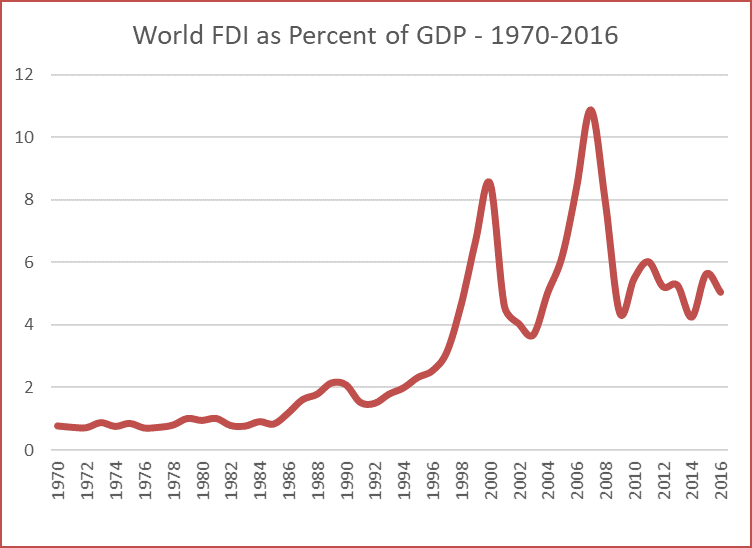

Globalization in the latter sense has stagnated or fallen in recent years. The first figure shows the ratio of world trade in goods and services to world GDP since 1970. You see three phases: a modest rise from 1970 to the early 1990s; a true boom in international trade in the post Cold War period, from the early 1990s to 2008 and the start of the world financial crisis; and a remarkable flattening since the crisis, with world trade growing at only about the same pace as world GDP. The second figure shows essentially the same picture for world foreign direct investment (FDI) flows: a big increase between the early 1990s and the 2000s, with a stabilization in the post-crisis period at around 5% of world GDP, though with much more volatility than trade.

Martin Sandbu hopes that trade is once more outpacing GDP growth in 2017, pointing to faster trade growth in the first quarter. "While nobody yet dares to trust that this good news will last, there are good reasons to be confident", he says.

Two points. First, it doesn't look like trade will actually outpace GDP in 2017. In September the WTO did indeed raise its forecast for world trade growth in 2017 to 3.6%. But that is just the same as the IMF's latest forecast for world GDP growth this year. So the ratio of trade to GDP will stay flat.

Second, and more interestingly, would it necessarily be such "bad news" if world trade and foreign investment ratios remained flat at around their current levels? One can readily think of the globalization boom between the 1990s and the mid-2000s as a one-off adjustment, when multinational corporations in advanced countries outsourced a chunk of their production networks to selected locations in East Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America, mainly in response to the fall of the Soviet bloc, the opening up of China and reductions in the most egregious border barriers to trade in other developing countries. With that adjustment behind us, there is no particular reason to expect or want a continuous, indefinite rise in the indexes of globalization. We could stop obsessing about globalization and concentrate on other, likely more important long run determinants of human welfare, such as the quality of national institutions and governance, education, health, environmental quality, and so on.